The January Illusion

The January Illusion

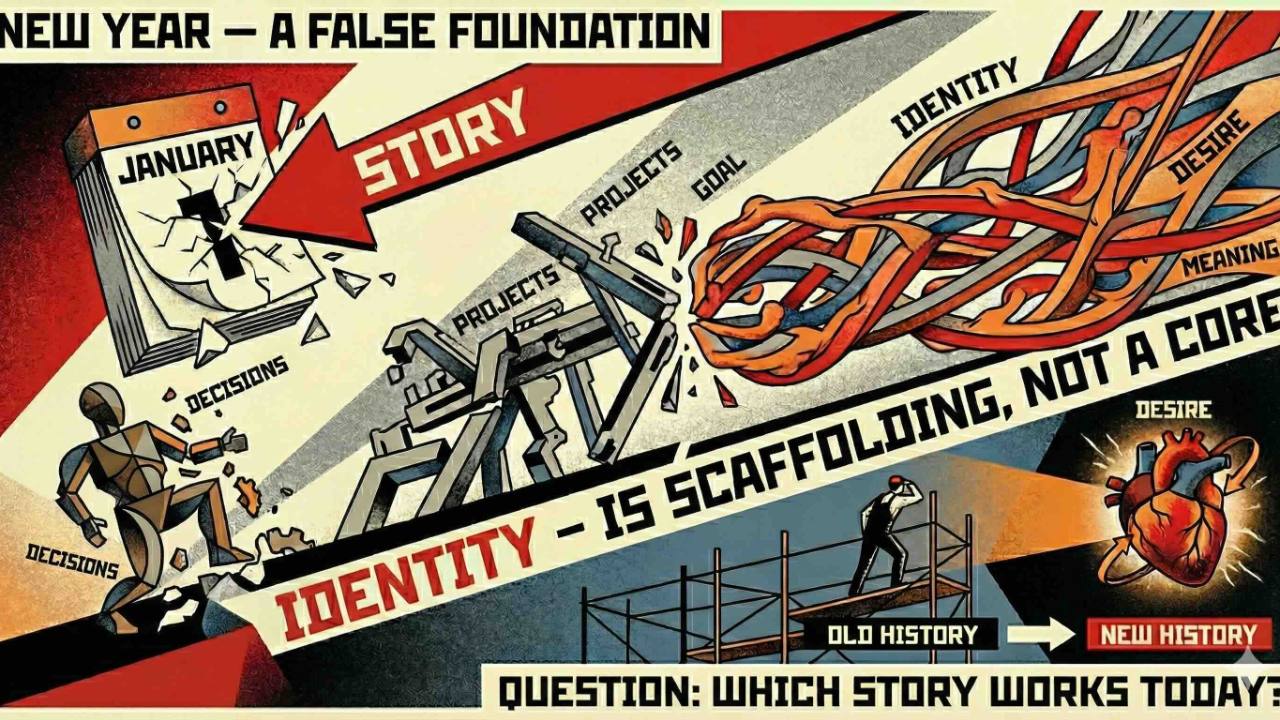

The annual ritual of New Year's resolutions rests on a flawed premise: that we can identify "right decisions" independent of the stories we're living inside. Most people approach January trying to fix a meaning problem with a purpose tool, expecting new projects to repair old narratives. Identity isn't a fixed core waiting to be discovered, but a scaffolding that evolves with life.

The useful...

The Long Return

The Long Return

On identity, home, and a considered holiday reccomendation

A reflection on identity as something unfinished, shaped by movement, memory, and delayed return. Drawing on my own life across countries, and on a formative encounter in the Hermitage, I explore how what we believe we have left behind rarely disappears. It waits.

This is also an excuse for two holiday recommendations, Julia Ioffe’s M...

The Happiness Shortcut

The Happiness Shortcut

The past week has been filled with articles promising “simple” routes to happiness. One in particular - a Washington Post piece summarizing a six-year Cornell study - argues that helping others might be the shortest way to increased well-being. The idea is appealing: turn outward, contribute, and the psyche steadies.

Yet the argument also reveals a familiar pattern. We keep mistaking purpose f...

(almost) Everything is Context

(almost) Everything is Context

Responses